Where Have All the Male Workers Gone?

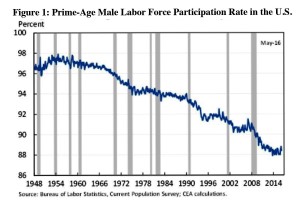

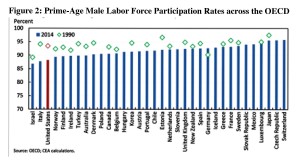

The White House Council of Economic Advisers has released a report showing a long-term decline in the share of American men ages 25-54 who are participating in the labor force  (see first chart), to the point where the U.S. now has one of the lowest male labor force participation rates in the world (see second chart).

(see first chart), to the point where the U.S. now has one of the lowest male labor force participation rates in the world (see second chart).

What’s going on? The traditional explanation is that many men are lazy, and prefer living on disability insurance and food stamps rather than actually getting off the couch and earning a living. But the study debunked this view, showing that the number of people receiving Social Security Disability Insurance has gone up by just 2 percentage points since 1967, compared to a 7.5 percentage-point decline in prime-age male labor force participation rates over the same period. Other government programs, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) have become increasingly hard to access for those out of work—and especially those without children.

Instead, the report cites a reduction in the U.S. economy’s demand for lower-skilled and less-educated men, whose participation rate has fallen the farthest, who are mired in jobs paying lower wages in an economy that is increasingly focused on technology, automation, and globalization. Another potential factor, compared with other developed economies, is the fact that the US spends just 0.1% of GDP on things like job search assistance and job training—far less than the 0.6% OECD average. Also, the US provides fewer subsidies for child care, has a higher tax wedge on secondary earners, and is the only advanced economy not to provide paid leave.

Instead, the report cites a reduction in the U.S. economy’s demand for lower-skilled and less-educated men, whose participation rate has fallen the farthest, who are mired in jobs paying lower wages in an economy that is increasingly focused on technology, automation, and globalization. Another potential factor, compared with other developed economies, is the fact that the US spends just 0.1% of GDP on things like job search assistance and job training—far less than the 0.6% OECD average. Also, the US provides fewer subsidies for child care, has a higher tax wedge on secondary earners, and is the only advanced economy not to provide paid leave.

One factor might come as a surprise: the Council of Economic Advisors speculated that the steep rise of mass incarceration since the 1970s in the US could be a contributing factor, even though prisoners are not counted in the statistics. People with a criminal record, even for drug possession or other victimless crimes, face substantially lower demand for their labor after they are released from prison.

In many States, the formerly-incarcerated are legally barred from a significant number of jobs by occupational licensing rules or other restrictions. Indeed, the American Bar Association has counted over 1,000 mandatory license exclusions for individuals with records of misdemeanors and nearly 3,000 exclusions for felony records. And there is evidence that, even in the absence of legal restrictions, employers are less likely to hire someone with a criminal record.

Whatever the causes, the chart suggests that the U.S. unemployment rate we see updated each month is at best misleading, because it doesn’t factor in the fact that fewer American men are participating in the labor force, and therefore represent an uncounted number of unemployed who quite possibly would like to have jobs, but know, due to lack of skills, training, education or a clean legal resume, that they are unlikely to find one.

Can anything be done? The report offers some possible remediations, including increased investment in public infrastructure (creating low-skill construction jobs); reforming community college and training systems to better match job demand; providing better search assistance as part of the unemployment insurance program; reducing the U.S. tax system penalty on secondary earners; expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit for individuals without qualifying children; investing in education and reforming the criminal justice and immigration systems.

Sources:

http://www.aei.org/publication/why-prime-age-men-leaving-labor-force/.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20160620_cea_primeage_male_lfp.pdf