Assets for the Long Run

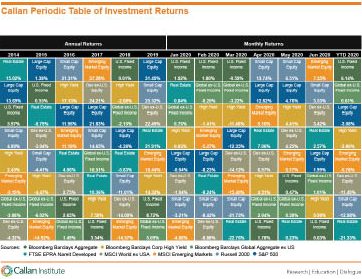

One of the most common educational props in the financial planning world is something known as the Callan Periodic Table of Investment Returns. The table is constructed in various ways—either with annual returns, or monthly returns—but the result for those shorter time periods is always the same and vividly illustrated. As you can see from the yearly and monthly return chart, the rank order of different asset classes (color coded; top is highest performers, lowest is worst returns), is always random.

See for yourself whether you can discern any pattern. That illustrates, better than words, that we really cannot predict whether international stocks will outperform domestic large cap or small cap stocks in any given year, or whether any of them will outperform various bond investments in the next 12 months. This explains why professionals recommend diversified portfolios. They simply don’t know, from one year to the next, which is going to perform better than what.

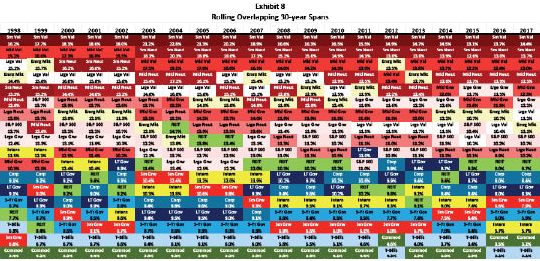

But the interesting thing is that if you look out over longer time periods, the returns are not nearly so random. In fact, when a professor of business analytics at the University of San Francisco, Stephen Huxley, constructed the same chart over rolling 30 year periods, he found that small cap stocks and value stocks pretty nearly always finished with the highest returns. You can see from the long-term Periodic Table that real estate investment trusts consistently fell in the middle of the pack, and the bond investments alternated places at the bottom of the long-term return chart.

What does that mean? To professionals, the striking consistency of this simple chart is strong evidence of something that is talked about but never actually proven: that over longer time spans, returns become more consistent and predictable than they are in shorter intervals, and that certain asset classes consistently, if unpredictably, provide more upside potential than others. A simple way to think of it is that as an owner of companies (buying stocks), you will eventually earn higher returns than if you are a lender to companies (buying bonds). You just have to wait long enough for the trend to play itself out.

Does that mean we should throw away the idea of diversification? Of course not. But it might mean that, if you have a long enough time horizon, you have a decent chance of earning higher returns if you overweight certain categories of stocks, and underweight bonds. You should still hold both and rebalance each year, which raises the odds of experiencing a smooth investment ride while you wait for the asset returns to sort themselves out over time.